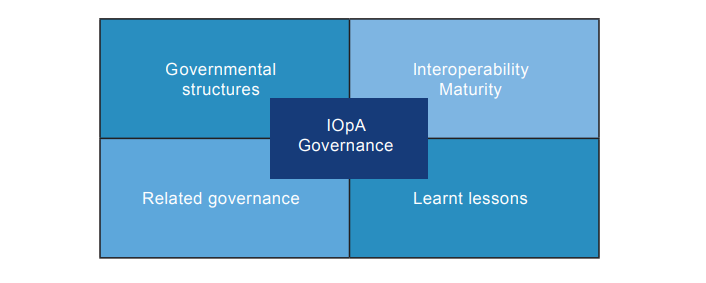

The following chapter gives advice on governance for different aspects of creating, implementing and managing interoperability assessments for the first time in an EU entity or a public sector body. Given the diversity of structures and processes in public organisation and the diversity of topics that can be addressed in an interoperability assessment (legal, technical, semantic and organisational questions), this chapter cannot offer a one-fits-all solution but it does highlight general messages. These are non-binding because it is up to EU and national competent authorities to establish or help establish the governance regime around the assessment processes as well to issue any additional guidance that might be desired. This chapter will dive deeper into:

- constituting a sound governance for assessments

- taking the specific context into account

- ensuring the sustainability of the process and mutual learning

- (soft) enablers for interoperability assessments

1. Constitution of sound governance

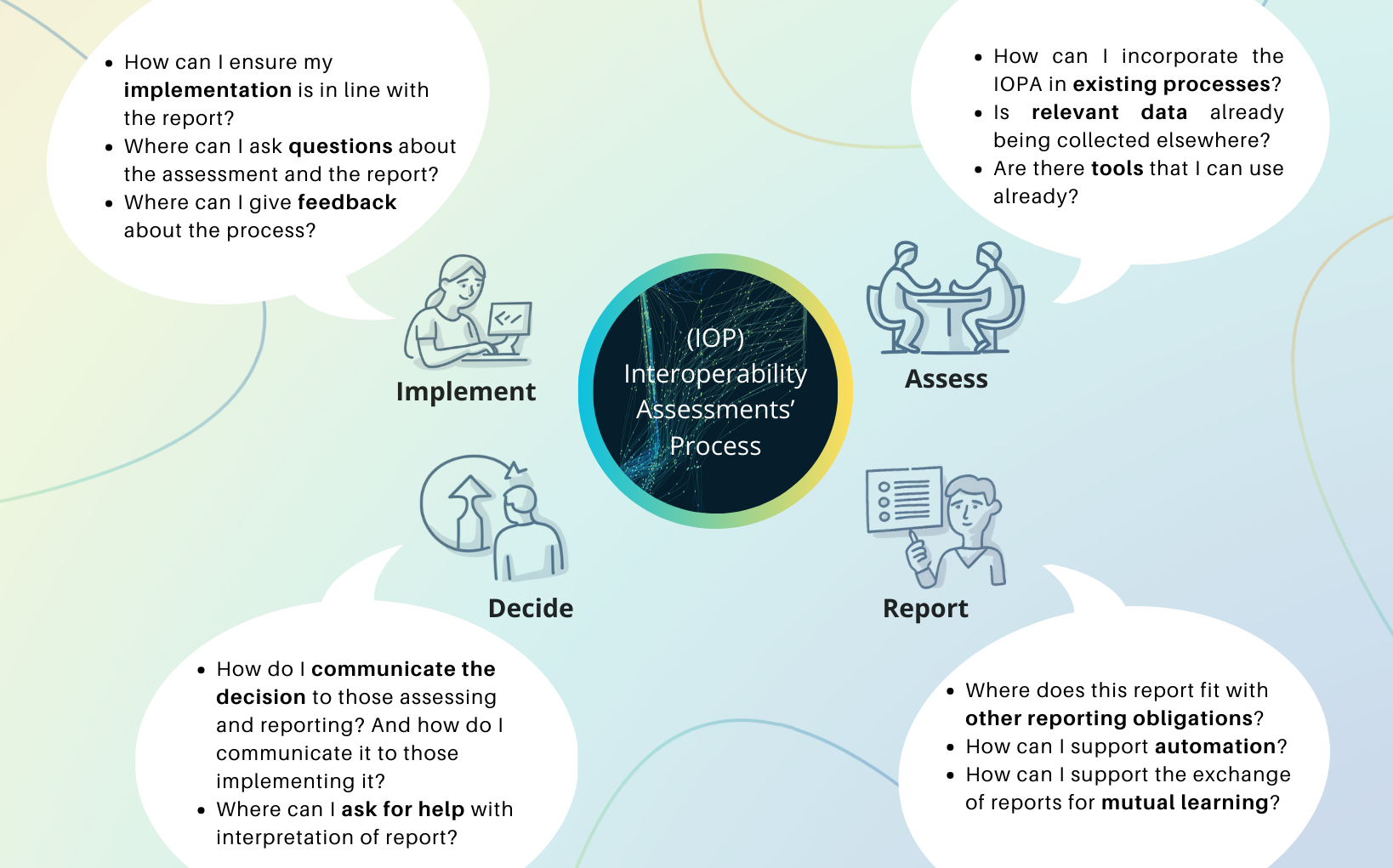

The IEA leaves the implementation of interoperability assessments to the administrative discretion of the public organisations concerned. This means that entities that conduct interoperability assessments can decide on the best process and its specificities – provided that they respect the common requirements set in Article 3 IEA.

When thinking about the governance of interoperability assessments in general, it is crucial not to view the interoperability assessment as an isolated exercise but rather as part of a larger ecosystem within the overall functioning of a public organisation (including policymaking processes, evaluation processes and the lifecycle of digital public services) and, in doing so, to link it to the governance of these processes and of the IT lifecycle.

This is part of the digital-ready policy-making mindset – the process of formulating digital-ready policies and legislation by considering digital aspects from the start of the policy cycle, ensuring that they are ready for the digital age, future-proof and interoperable. For example, in the cases mentioned in these guidelines, the cultural divide between the legal and the digital world may cause unexpected implementation costs since the effects of binding requirements were not considered early enough. Here, the digital-ready policymaking approach aims at reducing this divide by helping the best use of digital technologies and data to smoothly implement new requirements to their intended effect.

The starting point should therefore be to integrate the interoperability assessment into any existing processes. These can include consultation with stakeholders, digital checks or already existing assessment processes. Keep in mind that, the earlier the assessment is performed, the easier it will be to address any potential cross-border interoperability issues and thus improve the quality of the affected services. Therefore ensure, when establishing the process, that the assessment is conducted as early as possible.

Continuous governance of individual assessments might also be needed. Efficiently aligning personnel efforts with governance processes (involving various organisational levels) can significantly reduce the work required. To this end, Member States can decide themselves how to allocate internal resources and shape collaboration.

According to Article 17 IEA, each Member State’s single point of contact (SPOC) must support public sector bodies within the Member State in setting up or adapting the processes by which they carry out interoperability assessments. The interoperability coordinators in the Union entities have a similar task (Article 18 IEA). If you are unsure how to integrate the assessment process or about governance in general, consider contacting your SPOC to see if they have information on how other public organisations have chosen to set up the process. The Commission is also planning to collect good practices, training materials and other opportunities to exchange information on the Interoperable Europe portal.

2. Context dependency

The future setting of the assessment process depends very much on the context within which it is to be integrated. There are nevertheless some general points to be aware of.

Each public organisation will have to integrate the interoperability assessment into different governmental structures – some more centralised, some more decentralised. Especially in Member States with a federal state structure, there might be several competent authorities that will need to work together with their SPOC so that information can flow consistently. It is therefore important, when establishing the processes in a public organisation, to understand the particular government setting and to follow the guidance of the respective SPOCs or interoperability coordinators.

An organisation’s interoperability maturity also influences the interoperability assessment process. Organisations with higher levels of interoperability maturity may require fewer resources for these assessments due to existing strategies and tools. These can include the implementation of NIFs, IT strategies, reference architectures, core vocabularies or established consultation processes. If there are already interoperability assessment processes in place (e.g. you are using tools to assess the interoperability maturity of existing digital public services), consider how these processes and/or their results can be integrated into the interoperability assessment process. If this does not apply to you, see if you can combine the implementation of interoperability assessments with measures that would strengthen your organisation’s overall interoperability maturity.

You may identify certain processes within your organisation that are already highly interoperable. Regardless of whether the interoperability applies to the cross-border level or not, you should make sure to learn from these cases because the same mechanisms might be applicable to other use cases. It does not matter if a specific case does not match your use case perfectly; you can still adapt some parts of the process or examine these cases in order to gain a better understanding of interoperability and its related processes. Related assessments could also be found in the field of IT security or data protection, and serve as helpful examples.

Article 17(4) IEA requires Member States to set up the necessary cooperation structures between all national authorities involved in implementing the IEA. These can be based on existing mandates and processes. There may already be processes in place to take some decisions that legally, contractually or technically bind public organisations, and these processes may be subject to existing governance structures and procedures such as impact assessments. Try to identify the place of the interoperability assessment in these processes, e.g. by identifying other relevant assessments in order to find the most relevant entry point for interoperability assessments and to identify ‘sibling assessments’. Learning from similar assessments would also help you to determine whether it is necessary to conduct an interoperability assessment in your case or if the obligation has been fulfilled by a sibling or preceding assessment.

3. Sustainability, continuous improvement and mutual learning

Like any organisational process, the interoperability assessment process and its governance must be sustainable and improved over time. Methods such as the OODA (Observe-Orient-Decide-Act) loop or the PDSA (Plan-Do-Study-Adjust) cycle can help with this.

As you gain experience with interoperability assessments, take time to reflect on and document the lessons learnt for the entire process as well as the individual steps. What worked well? What challenges did you face? How can the assessment methods be refined? This reflection might prompt you to update your assessment approach so that future evaluations benefit from past experience. Consider creating a ‘lessons learnt’ document or updating your internal assessment guidelines to capture these insights.

To this end, also consider the implementation of the binding requirement. Even if you are developing your master plan of implementation very precisely, you might overlook aspects which could in practice impair implementation and the overall process. Install feedback loop mechanisms to communicate this information to the people who are actually carrying out the assessments. A welcome by-product is that you will spread the ownership of the whole assessment to everybody in the process chain. This should increase motivation and boost the quality of the results of the assessment. Feedback loops are also the basis for a continuous improvement of the process and should therefore go beyond individual interoperability assessments.

More advanced organisations can also use methods such as the OODA loop or the PDSA cycle. For example, the interoperability assessment governance could include a mechanism to observe the implementation of the adopted interoperability assessment process at each individual stage, the interrelationship of these different stages and one observation of the overall process (including its governance). These methods should be continuously examined with a view to improving the effectiveness and efficiency of the interoperability assessment process.

It is also important to share best practices and lessons learnt with other organisations. Interoperability is a collective endeavour and the exchange of knowledge can accelerate improvements across the entire EU public sector. Consider contributing to the Interoperable Europe Community or engaging in peer exchanges with other public administrations. The SPOCs and interoperability coordinators at national and EU level can play a facilitating role (especially in larger government structures that include several competent authorities).

4. (Soft) enablers

Some more general measures can also make a difference when implementing interoperability assessments.

When it comes to working on interoperability, the cultural aspect of organisations is also crucial. Interoperability is about working together, breaking down not only technical silos but also organisational silos. A specific mind-set is needed in order to recognise the value of interoperability. In this sense, interoperability assessments are more than technical processes because they can be pivotal in driving organisational change. Through these assessments, organisations gain a deeper understanding of how various systems interact and can make more informed decisions not only about IT developments but also about policy developments in general. When considering how to conduct an interoperability assessment, you should therefore also consider your organisation’s mind-set – and the extent to which its members are aware of and open to interoperability considerations.

Performing interoperability assessment requires specific skills that should be available in the team(s) that will carry out the specific assessment. In general, we recommend ensuring that you have multi-disciplinary teams, as the assessment might bring to light issues from different fields – everything from policy, to IT or legal questions (for inspiration see Issue paper on multidisciplinary teams | Joinup).

A multi-disciplinary team consists of individuals with varied expertise who work on the tasks at hand collectively. It can include experts on the specific subject (e.g., health, taxation, or education), legislative drafters, service designers, business rules specialists, etc. As a starting point for determining which profiles you might need, you can consider the different interoperability dimensions (legal, organisational, semantic and technical). It might be difficult for smaller public organisations to find suitable experts. It is therefore important to plan flexible support measures, which could go as far as the delegation of carrying out the interoperability assessments. However, the delegation does not imply the transfer of legal responsibility.

Also make sure that only relevant data are collected for the interoperability assessment in order to minimise data processing effort and resources. Make sure that the collected data can be reused as much as possible for related assessments and processes. Reuse as much as possible the tools provided by the Commission to automate these tasks. Complement them where necessary to maximise their automation.

Summary

In order to harvest the full value of interoperability assessments, it is necessary to establish a sound governance regime for the entire process. This should build on the integration of assessments in existing processes (whether these are well-established and obvious, or require some exploration). The SPOC in a Member State or the interoperability coordinator in an EU entity can facilitate the exchange of knowledge with other public organisations that are also establishing processes. It is important to consider the context in which these assessments take place because the government structure, existing governance processes that are related to the assessments or existing use cases might offer valuable insights as well as possibilities for reuse. It is also advisable to consider the organisational culture in which the assessment will be set as well as the existing skills.