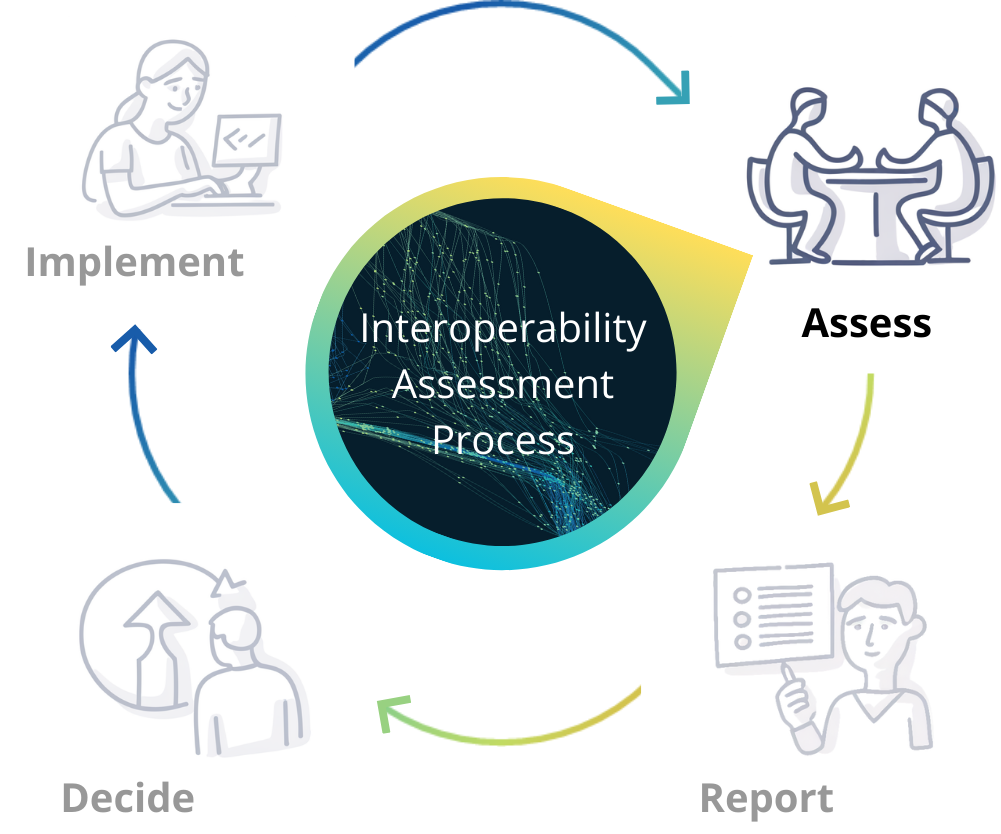

Having used the decision tree in Chapter 2 to determine that an interoperability assessment is required, this chapter will guide you through the process of conducting the assessment itself. This chapter aims to provide you with a clear step-by-step guide on how to conduct an interoperability assessment in accordance with the IEA. By the end of this chapter, you will know:

- the key steps involved in an interoperability assessment

- how to identify and document binding requirements

- how to detect effects on cross-border interoperability

- how to identify and consult with relevant stakeholders

- how to identify applicable Interoperable Europe solutions

The IEA clearly states that the approach to conducting interoperability assessments should be proportionate and tailored to their level and scope. This means that different methodologies and tools will provide different value in different contexts (see subsection 3.4 of this chapter). This chapter does not aim to provide a one-fits-all approach but to make you familiar with different options. These options differ according to circumstances that are linked to the overall interoperability governance of a public organisation. Such a governance could, for example, entail the existence of national or organisational assessments or IT/interoperability frameworks (see Chapter 5). If there is no specific guidance on the approach for interoperability assessments in a specific organisation, the person leading the assessment should choose the approach that brings most value while creating least burden.

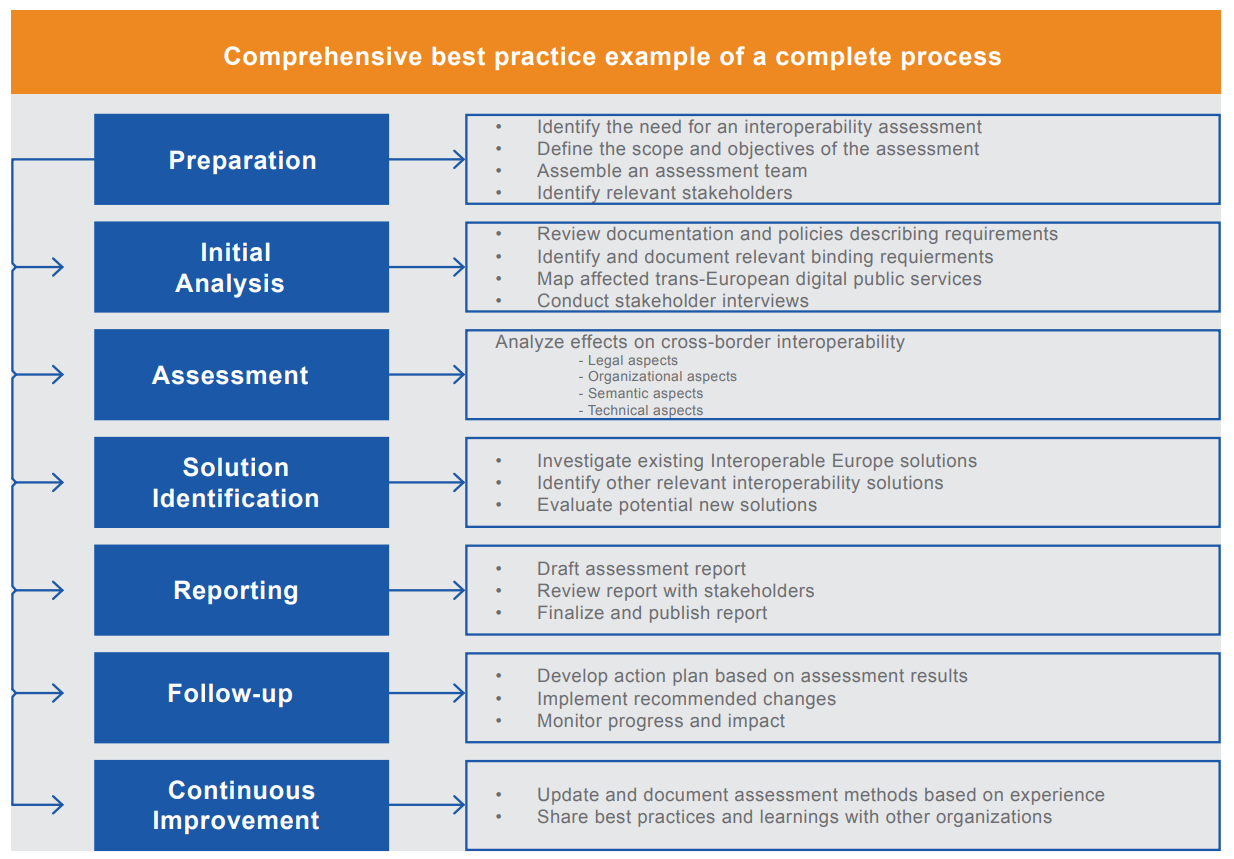

The process outlined in this chapter represents a comprehensive ‘best practice’ approach to interoperability assessments, but we recognise that organisations vary in size, structure, resources and maturity levels. This process can and should be tailored to fit your specific organisational context and constraints.

The key is to maintain the core principles of the assessment while scaling the process so that it is both manageable and meaningful within your particular circumstances. As you progress through this guidance, consider how each step can be adjusted to align with your organisation’s capabilities and requirements – ensuring that the assessment remains valuable and actionable, regardless of your starting point or available resources.

The first step is to explore the general recommendations for conducting an interoperability assessment, before diving into each step of the process in more detail.

3.1 General Recommendations

General recommendations to find the right approach:

Start early

The greatest returns are obtained when assessments are performed early in the design of new binding requirements (e.g. as part of policy design, legal proposals, or the design of new IT solutions) and, at the latest, before taking binding decisions.

Be fit-for-purpose

The more precise and unique the decision that contains the requirements (e.g. a single project implementation of a local authority), the more pragmatic and therefore narrower the focus of the assessment can be. Try to clearly define your scope and objectives, and to adapt the assessment to them.

Build on the existing frameworks

The assessment should be aligned with existing organisational and administrative frameworks, thereby ensuring that they complement the administrative workflow. Where applicable, legal frameworks regarding digital policies should be considered as well. If the assessment is linked to a prior (EU or national) assessment, reuse that prior assessment and build on it.

Consult with stakeholders

Conducting an interoperability assessment should involve consulting the directly affected service recipients (including citizens or their representatives). It would also be advisable to consult implementers as well as other actors involved in the provision of the service. Keep in mind that such assessments may involve individuals that do not have a background in information management or IT.

3.2 Preparation

This stage sets the foundation for the process, helping to define the scope, assemble the right team and establish a clear plan of action. By investing time in this initial phase, you can streamline the subsequent stages of the assessment, avoid potential pitfalls and ensure that the final results are both relevant and implementable.

The decision-making procedure for this step is described in detail in Chapter 2. In particular, the decision tree in that chapter sets out a structured approach to evaluating whether an interoperability assessment is required in your specific case. You should only proceed with the subsequent steps outlined in this chapter if the Chapter 2 preliminary evaluation indicates that an assessment is needed. Nevertheless, even if you are not legally obliged to carry out an assessment, you can still do one voluntarily.

Defining the scope and objectives of the interoperability assessment shapes the rest of the process. The scope determines the boundaries of what will be assessed (including which instance(s) of data exchange, systems, processes or services will be examined and in what depth). Objectives clarify what you aim to achieve with the assessment (e.g. identifying specific interoperability gaps or evaluating compliance with certain standards).

It is important to remember that the scope and objectives should be tailored to the specific context of your project and organisation. Consider the nature and complexity of the project being assessed, as well as the organisational structure and available resources. A large-scale cross-border initiative may require a comprehensive assessment. A smaller, localised project may benefit from a more focused approach.

When defining scope and objectives, reflect on your organisation’s capacity to conduct the assessment. This includes not only financial resources but also time, expertise and access to necessary information. The goal is to strike a balance between thoroughness and practicality, ensuring that the assessment is both meaningful and manageable within your constraints. Given all this and while the assessment must always concern a trans-European digital public service, be aware that the scope and objectives can therefore vary greatly not only between Member States and Union entities, but also within your Member State and within your organisation.

Assembling the right team is crucial for conducting an effective interoperability assessment. The ideal scenario would involve a diverse group of experts, but we recognise that organisations may have limited available skills and resources. The key is to strive for the best possible combination of competencies within your constraints. In an ideal scenario, your assessment team would combine multiple sets of skills and perspectives. Consider including team members with expertise in areas such as:

- legal and regulatory aspects of data exchange (interoperability)

- business process analysis

- data management, including semantic expertise and governance

- IT architecture and systems integration

- specific domain knowledge relevant to the binding requirements being assessed and services affected

Remember that one person may be qualified in multiple areas of expertise. If resources are limited, prioritise the most critical skills for your specific assessment context. You might also consider temporarily bringing in external experts or consultants to fill any crucial gaps in your team’s expertise. The size of your team should be proportionate to the scope of your assessment. A small focused team might be sufficient for a limited-scope assessment. A larger and more complex project may require a more extensive team.

Start identifying the stakeholders for whom the binding requirements could be relevant, e.g. by asking yourself who might be affected by it in:

- implementation, e.g., who is involved for which part of the process?

- service provision, e.g., which organisations are necessarily involved for successful delivery?

- delivery itself, e.g., who must interact with whom?

- or management, e.g., who is involved to ensure consistency?

They can be public or private stakeholders (businesses), citizens or Union entities. These stakeholders will need to be consulted at a later stage. If such stakeholders are identified early, they might even already contribute to carrying out the next step (e.g. identifying the binding requirements). It is not required to identify each individual stakeholder but rather to identify the categories (e.g. all citizens or just a particular group, all businesses or just specific sectors).

3.3 Initial analysis

The next stage involves examining existing documentation, policies and services in order to identify and understand the key elements that will shape your assessment. This stage has three purposes:

- to gather and review relevant documentation and policies that describe the requirements affecting interoperability;

- to identify and clearly document the binding requirements that are central to your assessment;

- to map out the trans-European digital public services that are affected by these requirements.

As you progress through the following three subsections, remember that the depth and breadth of your analysis should be proportionate to the scope of your assessment as defined in the preparation phase. The goal is to create a solid foundation of knowledge that will inform the rest of your assessment process.

The primary purpose of this stage is to gather and analyse all documents that are relevant to understanding the new or modified requirements (whether they are explicitly stated or merely implied). This review is the basis for identifying the binding requirements central to your assessment in the next step.

It is important to note that the nature and extent of available documentation can vary significantly, depending on the current phase of the project or initiative being assessed (whether that is in the legislative preparation phase, the concept and design phase or a later phase).

Depending on your current stage of the process leading to the development of a digital public service, the following might be an outline of possible steps to take.

- Identify and collect all relevant documents. These can include not only the legal acts that set the requirement, but also secondary sources such as technical documentation or communication about the document containing the requirements. Cast a wide net initially in order to ensure that no crucial information is missed, e.g. go beyond the binding document describing the requirements and consider Review documentation and policies describing requirements the context in which they are set or will be implemented. This can include other, existing obligations on data exchange that are not currently being regulated on;

- Categorise the documents based on their type and relevance to interoperability.

- Perform an initial review to understand the scope and content of each document.

- Create a summary or index of key documents and their relevance to interoperability requirements.

- Identify any gaps in documentation that may need to be addressed.

Other considerations:

- consider both internal and external sources of documentation;

- pay attention to version control, ensuring that you are working with the most up-to-date information;

- look for references to standards, or other external requirements that may impact interoperability

- take note of any ambiguities or inconsistencies you find in the documentation for further investigation.

Remember, the goal at this stage is not to analyse the requirements in depth, but to create a reasonable overview of the documented landscape. This will serve as the basis for the more detailed analysis in the following steps.

The purpose of this step is to identify and document the binding requirements that you are planning to assess (please refer to Chapter 2 for more information on what a ‘binding requirement’ is). Please note that a single interoperability assessment may also be carried out to address a set of binding requirements (usually when they are all to be set by the same decision-making process).

You will need to document the requirements because they will help you in the discussion on the impacts of these requirements, which is the aim of the interoperability assessment. Keep in mind that this exercise is not always straightforward. Some requirements might not directly be obvious and explicit but may only be identified after a thorough and expert analysis.

Examine the documents you have already identified and extract the binding requirements that:

1. concern a digital public service:

- they have a digital dimension, i.e. when their underlying processes are digitalised or automated; they deal with data; they involve the setting or use of digital solutions; they offer a digital channel for service delivery; or are provided via network and information systems

- they involve interaction between public organisations, i.e., they are provided by Union entities or public sector bodies to one another or to natural or legal persons in the Union

2. have a trans-European dimension:

- they require interaction across Member state borders, among Union entities or between Union entities and public sector bodies

Be thorough in your considerations: If the existence of a binding requirement is missed in the assessment process, it can sometimes lead to cross-border interoperability issues for implementers later on. For example, missing interoperability requirements were in the past a trigger for rethinking the policy approach for eInvoicing - Report on the effects of Directive 2014/55/EU on the Internal Market and on the uptake of electronic invoicing in public procurement (European Commission).

After you have identified the requirements, you can choose the method that works best for you to document the identified requirements (the EU open data portal offers a detailed Data Visualisation Guide which includes diverse techniques from charts to graphs and storytelling). In general, avoid using the passive form when documenting requirements, because this often results in the actors (i.e., those who are involved) not being clearly identified. Make sure that the extract includes the information necessary for it to qualify as a binding requirement because your assessment may have involved information gathered from the context of the binding document (not the document itself).

Depending on the stage of a project in which the requirements are set, different methods to identify and document requirements can be valuable (e.g. looking to user stories or use cases at the beginning of the legislative cycle). So, when documenting your identified requirements, consider the expected audience for the interoperability assessment. While the assessment must be published on an official website, e.g. be publicly available, it will most likely also inform the subsequent processes within the life-cycle of a digital public service. Therefore, consider whether the assessment report will be shared with others as is or whether you will draw up a different document for e.g., stakeholder consultations, procurement or implementation. If yes, adjust your methods accordingly. Your documentation will also depend on the type of binding requirements you are describing (e.g. business, functional and non-functional requirements, or technical requirements).

As mentioned above, your requirements will generally be part of a larger process, of which they regulate only certain parts. It therefore makes sense to look at the wider overall process and adapt your documentation to its specificities. To this end, you can:

- translate the requirements into a process diagram;

- list the requirements in a form that is reusable (e.g. for a call for tender). In cases where the interoperability assessment is linked to the procurement of ICT systems, technical specifications of the procurement files should meet the requirements defined in ICT technical specifications to be eligible for referencing in public procurement, which can be considered interoperability solutions.

To assess where and how the identified binding requirements will affect the trans-European digital public service, it makes sense to concentrate on visualising the service itself, including its trans-European dimension (e.g. the connection across Member State borders, among Union entities or between Union entities and public sector bodies, by means of their network and information systems). The purpose is to identify and visualise the cross-border data exchanges and interactions required for the public service to be provided effectively. This way, you can prepare the way for an assessment of the effects of the requirements on cross-border interoperability., i.e. precisely on the data exchanges and interactions identified before.

There are many ways to approach this task, but the following section outlines one possible way to understand both the service itself and the interactions across borders which then give rise to considerations regarding interoperability.

First, visualise the service itself by considering the following:

- What is the overall goal of the linked decision? (relevant context and orientation point)

- Who is involved? (actors such as businesses, citizens, etc.)

- What happens? (Checking data? Issuing evidence?)

- When does it happen? (temporal dependency? Process dependency?)

- Where does it happen? (back office? Databases? Specific (physical) location?)

- Why does this happen? (legal basis, incl. possible subsidiarity)

You can do this visualisation in different ways (e.g. as a user journey, a decision tree or a process diagram). You can also map the requirements in a tool to visualise service architecture (e.g. using the European Interoperability Reference Architecture (EIRA)). For the trans-European dimension of the digital public service (e.g. the cross-border connection needed between public organisations in order to provide the service in question), consider the following points in order to map the identified requirements to the service.

| 1.Identify required data exchanges: |

|

| 2.Identify collaborating services: |

|

| 3. Characterise the interactions: |

You can then also map the connections as well. |

| 4.Create a visual representation of these interactions: |

| Such visualisations, e.g. an architectural diagram, will also add significant value to the further assessment process. For the first step, you can use flow diagrams, user journeys or other methods of visualisation. After mapping these connections, it is also important to consider what implementing the binding requirement would mean specifically. You should therefore also pay attention to the following points. |

| 5.Identify dependencies: |

|

| 6.Consider scalability: |

The output of these efforts might be a map or diagram showing how your public service interacts with other services across borders. This could include:

|

These mappings could serve as a reference point for the assessment process, helping to identify potential interoperability challenges or requirements. For example, you could use them to consult with stakeholders and together find inconsistencies (logical, legal or formatting/documentation), open ends or duplications. They will also show dependencies on other services, organisations or processes that could be affected when deciding on the binding requirement in question.

The list of stakeholders put together in the preparation phase should be refined at this stage of the assessment. Consultations can be used for several purposes: they can help refine the documentation of the requirements and the concerned services (as mentioned above). They can also help you to better explain the issue at stake to the stakeholders and can help assess opportunities for better cross-border interoperability in the future. As the focus is on trans-European digital public services and their cross-border interoperability, two stakeholder groups are particularly relevant for the assessment:

- Users of digital public services: service recipients (natural or legal persons) that rely on the interaction of digital public services across borders to effectively use these services. Conducting an interoperability assessment requires consulting these service recipients (including citizens or their representatives) in order to assess possible impacts. This provides valuable feedback on the proportionality of the binding requirement in relation to the original goal of its introduction (i.e., is this requirement proportionate to the expected benefit of its introduction?). It also makes it possible to gauge the effectiveness of the requirement (i.e., will the binding requirement help achieve what it was set for?). The requirements can therefore be adapted accordingly before a binding decision is taken. Keep in mind, however, that such assessments may involve individuals who do not have a background in information management or IT, and to adjust your communication accordingly.

- Public organisations in other Member States or at EU level are Union entities or public sector bodies that regulate, provide, manage or implement trans-European digital public services. They include stakeholders from the entire lifecycle of the service (e.g. policy officers, IT implementers and other affected user groups inside the public organisation, such as service providers). If you are not sure how to consult these stakeholders, you can also consult Chapter 7 in the European Commission’s Better Regulation Toolbox. Be aware that to ensure interoperability, it might be necessary to deep dive into specific policy fields. Another example of stakeholder consultation could therefore be to consult experts in these fields. Also keep in mind that the requirement of Article 3 IEA to carry out consultations does not mean that those consultations have to be conducted in addition to consultations that are part of other processes. Integration with existing processes is possible and, indeed, very much encouraged in order to exploit available synergies (see Chapter 5). The stakeholders’ involvement can go beyond this initial phase and you can also validate the outcome of the next step (assessment) with stakeholders.

4. Assessment of cross-border interoperability

Having established the basis for your assessment, we now move to the core of the interoperability assessment process. This stage involves an evaluation of the effects of the binding requirements on cross-border interoperability from multiple perspectives in accordance with the EIF. In the following subsections, we will explore how to analyse the effects on cross-border interoperability – considering legal, organisational, semantic and technical aspects – and provide best practice examples for how to approach this task

4.1 Analyse effects on cross-border interoperability

The IEA does not prescribe one mandatory method, but it does state that the EIF is a supporting tool (Art. 3 (2) IEA). As explained above, it is necessary to keep in mind that the assessment does not need to show the way towards full interoperability, but it should help detect ways towards more interoperability. If your public organisation has already decided to use one method for assessments, please follow this decision (see Chapter 5). Taking the EIF as the main starting point for your assessment means considering the extent to which the proposed requirements enable or hinder interoperability. This could also show whether additional requirements are needed. Recital 21 states that the assessment should evaluate the effects of the planned binding requirements having regard to the origin, nature, particularity and scale of those effects. In order to pay attention to these, the four dimensions of the EIF can be a first starting point.

The aim is to assess the extent to which the binding requirements allow public organisations operating under different legal frameworks, policies and strategies to work together to provide trans-European digital public services. This assessment should consider factors such as the consistency of the requirement with existing laws and regulations; the potential for conflicts or inconsistencies with other legal frameworks, including EU digital policies; and the feasibility of implementation and enforcement.

The aim is to assess the extent to which the binding requirements do or do not help public organisations in aligning their business processes, responsibilities and expectations to achieve a high-quality, seamless provision of the trans-European digital public services. To what extent do the binding requirements create opportunities or risks for organisations and the way they work? Are they for example setting new tasks that need to be incorporated or are they (re-) allocating responsibilities?

The aim is to assess the extent to which the binding requirements ensure that the precise format and meaning of exchanged data and information are preserved and understood at all stages of the exchange needed for the provision of the affected trans-European digital public services. To what extent do the binding requirements create opportunities or risks for the meaningful exchange of data across borders? Are they for example encouraging the use of controlled vocabularies or are they using new concepts?

The aim is to assess the extent to which the binding requirements help the different parties to securely and properly interconnect so that they can provide the trans-European digital public services.

| As of this version of the guidelines, there is not one tool that would cover all these aspects. Currently, there is a first version on the Interoperable Europe Portal with which your results can be reported in the format prescribed in the annex of the regulation. For now, the following example can give a first idea of the necessary questions to enable cross-border interoperability and therefore the first intervention points for identifying possible effects of the binding requirements on cross-border interoperability. |

| Example: Citizens with disabilities are still facing issues when using their national disability card in other EU countries. It is clear that these issues must be overcome. National disability cards should ideally become digital, but this raises some difficult interoperability questions. For example: |

| 1. Legal |

|

| 2. Organisational |

|

| 3. Semantic |

|

| 4. Technical |

|

4.2 Best practices for detecting effects on cross-border interoperability

We present below some different approaches that are all based on the EIF and can be used as supporting tools when performing the assessment on cross-border interoperability. All these approaches comply with the legal requirement to perform the assessment in an ‘appropriate manner’

Binding requirements in legal texts are often not written within a multidisciplinary team, so knowledge of some aspects of digital implementation may be lacking. In such cases, the assessment is more of a discovery exercise in which the actors find out that the policy contains binding requirements and they become aware of subsequent implementation consequences that they might not have considered before. Furthermore, policies can be implemented in very different ways and are in many cases not even intended to be prescriptive as to the manner of implementation. This means that interoperability assessments on policies face two additional challenges:

- the people drafting the requirements might have little knowledge of digital implementation;

- many questions on digital implementations might still be very open because the process is still at its very beginning.

To address these challenges, the Commission and several Member States have in recent years translated the EIF into practical checklists that are easier for policymakers to understand and answer (examples include practices in the Commission Tool #28 in the European Commission Better Regulation Toolbox; Denmark Digital-ready legislation; and Germany Digitalcheck: refining the beta version step-by-step). These questionnaires can be a starting point for policymakers wishing to discover how a policy can improve cross-border interoperability or risks that create new challenges for cross-border data flow. They can also guide policymakers on further steps to take when diving deeper into open issues (e.g. by involving experts with other professional backgrounds).

The work related to the single assessment can be easier if the organisation already has an overall interoperability governance aligned with the EIF. In this case, it is not necessary to take the EIF as a starting point to perform the assessment. Using the specialised interoperability frameworks (e.g. a NIF or a sectorial interoperability framework) to perform the assessment allows more value to be created and might make the approach more straightforward. The following are examples of interoperability governance processes that are aligned with the EIF and that you might recognise from your own experience.

- Some Member States have ‘transposed’ the EIF into a national interoperability law and added requirements that are specific to their Member State’s context. Examples can be found in the National Interoperability Framework Observatory NIFO. In such cases, the assessment can examine how the binding requirements would fit into this set-up.

- Some Member States have introduced national interoperability reference architectures that are aligned with the EIF (some of them are based on EIRA, such as Poland, as well as Malta). The assessment could examine how the requirements fit into such national architectures.

- Some Member States have introduced data governance frameworks that incorporate the recommendations of the EIF. The assessment can be based on such practices.

- Some international organisations, like the World Bank, have used the EIF as a guiding principle for their initiatives, such as ID4D (Identification for development) which aims to help practitioners design and implement identification (ID) systems that are inclusive and trusted.

Questions related to alignment with a national or specialised framework could include:

- how do the requirements fit into the interoperability governance in my organisation?

- how do the requirements fit into the architectural set-up?

- have we documented the affected data flows, as required by our national interoperability set-up?

This starting point is relevant for all organisations that do not have a dedicated method for (interoperability) assessments or do have such a dedicated method but not one that is aligned with the EIF. It is also a valuable approach to assess the binding requirements more specifically (e.g. for checking compliance with a standard).

Several solutions have been developed to support an EIF-based assessment for different purposes. All these solutions will need to be adapted in order to fully support the interoperability assessments in the future, but they can already provide some helpful guidance today. If the assessment shows a high score, the effect on cross-border interoperability should be positive; a low level of alignment should trigger a low score. The following are examples of such tools.

For assessments that concern a change to an existing digital public service: the Interoperability Maturity Tools (IMAPS, SIQAT and GIQAT). These are self-assessment tools to evaluate the interoperability maturity of digital public services at all government levels. They therefore offer valuable starting points but would need to be adapted as interoperability assessments are concerned with binding requirements, not specific digital public services. If choosing such a solution, online questionnaires to score interoperability maturity should be provided along with recommendations for the report.

- For assessments that concern a standard or a specification: CAMSS is a self-assessment tool to evaluate the interoperability support of chosen standards and/or specifications. An online questionnaire to score interoperability should be provided for the report.

5. Solution identification

A key principle emphasised in the IEA is the importance and value of reusing existing interoperability solutions (e.g. standardised building blocks or core vocabularies) to promote interoperability, harmonisation and effective use of public resources. This approach not only enhances cross-border interoperability but also contributes to cost-efficiency and consistency between public services in the EU.

The IEA states that organisations must, during the interoperability assessment process, evaluate the applicability and therefore reusability of existing solutions, and particularly those designated as ‘Interoperable Europe solutions’. These are interoperability solutions (e.g. standards, building blocks and core vocabularies) that have been vetted and recommended by the Interoperable Europe Board for their potential to improve or establish (cross-border) interoperability where needed.

The following are the primary objectives of this stage:

- to identify relevant Interoperable Europe solutions that could address the interoperability needs identified in your assessment;

- to evaluate how these solutions could be integrated into your service in order to enhance interoperability;

- to consider other catalogues of reusable solutions, whether at EU or national level, that might offer suitable approaches.

By prioritising the reuse of existing solutions, the development of interoperable services can be accelerated, duplication of effort can be reduced, and alignment with established standards and practices across the EU can be ensured.

In the following subsections, we will explore how to effectively identify, evaluate and potentially adapt these solutions in the context of your specific service and interoperability requirements

As briefly mentioned above, Interoperability Europe solutions can be any reusable asset concerning legal, organisational, semantic or technical requirements to enable cross-border interoperability. Examples would include conceptual frameworks, guidelines, reference architectures, technical specifications, standards, services and applications, as well as documented technical components such as source code. Interoperable Europe solutions are interoperability solutions that have been recommended by the Interoperable Europe Board (expected in 2025).

The Interoperable Europe Portal (formerly Joinup) will eventually give access to all Interoperable Europe solutions, which will be marked accordingly and accompanied by corresponding search functionalities. The portal will further facilitate the search for other relevant solutions, including open-source solutions. However, many solutions are already available on the portal. National portals can also serve as entry points where you can look for reusable solutions that enhance interoperability. If you want to keep yourself informed about solutions that might become relevant in the future, consider joining relevant communities where you will also find more information and can join discussions.

When evaluating and selecting from the identified solutions, the concrete objectives of the assessment identified in the first stage should be recalled. In general, this part of the assessment is performed in order to increase the chances for interoperability in the future when the requirements are implemented. A common feature of Interoperable Europe solutions and interoperability solutions is that they can both be reused. Identifying reusable solutions early in the process can help to design requirements or adapt them in a way that would allow the reuse of these solutions and thus allow cost savings when implementing the requirements.

However, the assessment can in this step follow quite different agendas, including:

- exploration: keep things open enough to reuse (e.g. an Interoperable Europe solution);

- information: inform implementers through the assessment report of existing solutions that are potentially usable for implementation;

- planning: document the need to develop a reusable tool.

The solutions that are listed in an assessment report are not automatically binding for implementers. However, they can help implementers align and connect in their implementation efforts, save resources and automatically contribute to higher interoperability throughout the EU. To this end, you should not only assess whether and where reuse is possible but also, depending on the case, either make clear which solution(s) could or should be reused or if a new solution has to be developed. If possible, you could also contact your stakeholders again to check your results and get their feedback on possible solutions.

6. Reporting

Having completed your assessment of interoperability implications and identifying potential solutions, your next step is to document your findings and recommendations in an assessment report. This report is a key deliverable of the interoperability assessment process. On the Interoperable Europe Portal, it will be possible to fill in your report based on the information mandated by the Annex of the Act.

The specifics of drafting, reviewing and finalising the report are important, but they fall outside the scope of this chapter. For a detailed guide on how to structure and compile your interoperability assessment report (including specific requirements for content and format), please refer to Chapter 4 of this guide, where you will find instructions on creating a clear and informative report that can be acted upon and that meets the requirements set out in the IEA.

7. Follow-up

The completion of the interoperability assessment and the production of the report fulfil the mandatory requirement to perform an interoperability assessment. To draw the maximum benefit from performing the assessment, however, the conclusions and findings should be followed up – by making recommendations, communicating information on findings or taking concrete action.

The follow-up phase may also reveal new challenges or opportunities that were not apparent during the initial assessment. It is therefore important to remain flexible and to be prepared to adjust the action plan to reflect on actual real-world results and emerging insights.

Following through on the assessment findings allows organisations to ensure that interoperability assessments lead to meaningful improvements in the delivery of trans-European digital public services.

Summary

This chapter has outlined a comprehensive process for conducting an interoperability assessment, providing a detailed roadmap from initial preparation through to continuous improvement. The process described is a best practice approach that is suitable for complex projects that require a thorough evaluation of interoperability implications.

It is important to recognise that this detailed process serves as an ideal framework that provides a complete picture of what a full-scale interoperability assessment might entail. We nevertheless understand that not all projects or organisations will require or have the resources for such an extensive assessment.

As emphasised at the beginning of this chapter, the interoperability assessment process should be adapted to suit the specific needs, constraints and characteristics of your organisation and project. The scope and depth of your assessment should be proportionate to the scale and potential impact of the initiative you are evaluating.

Organisations should feel free to scale and tailor this process to meet their particular circumstances. This might mean focusing on certain phases more than others, combining steps or adjusting the level of detail in the analysis based on available resources and the complexity of the service being assessed. The key is to respect the core principles of the assessment while ensuring that the process remains manageable and delivers valuable insights within your specific circumstances.

An unpacked example of a best practice process is summarised in the following figure.