In a process spanning ten years the Munich city administration has migrated from a proprietary, vendor-locked IT structure to a free, open-source and flexible Linux-based solution. Although this could save the municipality millions of Euros, other reasons and benefits make the changeover even more attractive.

The fact that Munich was the first project of its size to move to Linux made the migration process more difficult than others which followed. But in the end, Munich now knows its IT resources better than ever. The municipality is able to control, organise and manage IT centrally; has systems in place for project, test, release and patch management; and is free from software licenses. And as a bonus, because the solution is free and open source it can and will be shared with Munich's citizens and fellow municipalities.

“LiMux – the IT evolution”: an open source success story like never before

More than ten years ago the city of Munich took a decision that was bound to put its IT administrators in the spotlight. At that time it was clear that Microsoft would soon stop supporting Windows NT 4.0, the operating system that ran most of the more than 10,000 desktop machines in the Bavarian capital. The IT specialists and politicians in Munich had to decide: a migration was inevitable, but to where?

In May 2003 the city council decided to migrate to Linux, beginning with a one-year concept phase. As experience over recent years has shown, the decision in favour of LiMux (Linux in Munich) marked a turning point not only for IT systems in the city of Munich, but also for administrations all over the world. And the lessons learned should become a blueprint for other big migrations in the public sector.

|

| LiMux, the “Munich IT evolution”, replaced Tux, the Linux penguin, with Mux, his Munich cousin. Mux proudly bears the “Münchner Kindl”, symbol of the city. © LiMux Project |

In 2013 the project was finalised and the acceptance documents signed. By that time 15,000 seats had been migrated to Linux and LibreOffice, centrally managed by open source tools that comply with open standards.

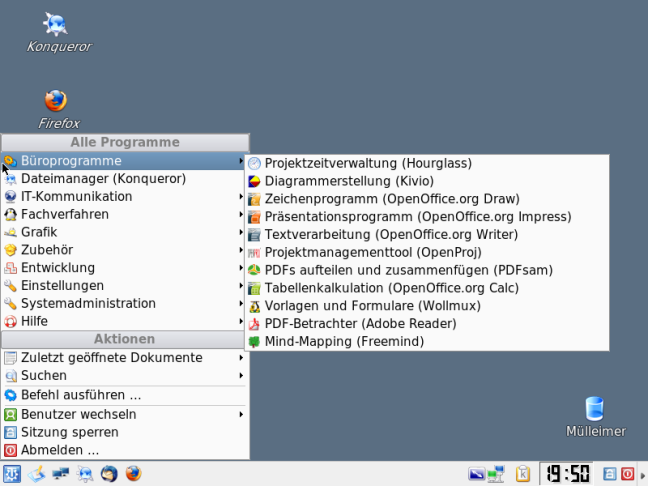

Today, the LiMux project consists of four main technical components: */ /*-->*/

- a Linux Basis Client with automated deployment and configuration management

- office software adapted for team working on Linux and Windows clients

- WollMux, a template and form manager

- necessary server components for the first three items

The city of Munich claims to have saved several million Euros as well as gaining freedom of choice, strategic independence, and acceptance throughout its departments. Bonuses that are harder to quantify, but also important, include better project, quality and change management, software testing tools, central deployment, key and sign-in services, and other administrative tools and systems that had not been in place before 2003.

Peter Hofmann, LiMux project leader, and Jutta Kreyss, IT Architect for the City of Munich's Linux desktop, stress repeatedly that most of these achievements are not included in the financial savings documented by various studies – yet on a proprietary software path they would all have had to be bought and licensed from external companies.

Along the way the municipality also had to develop strategies to convince employees, train and motivate their IT staff. From both a technical and a social point of view, Munich was a first mover and the eyes of many other municipalities lay on the Bavarian capital. As Peter Hofmann said: “It's like penguins in Antarctica. Do you know how they find out whether there are Orcas in the water? They keep pushing from behind. If the first ones survive, it's safe for the others to jump, too.” At one point the LiMux project even had to establish a dedicated communications team simply to answer questions from other cities. And of course a change management system had to be installed to push through the necessary project management and organisational changes.

All's well that ends well

After more then ten years of work, in autumn 2013 Hofmann was able to announce: “LiMux is done, we have surpassed most of our goals and for several weeks now we have been running in regular operations mode.” Hofmann and one of the several Munich mayors, Christine Strobl (SPD), signed the final project acceptance documents on 30 October 2013.

|

| LiMux project leader Hofmann and Munich Mayor Christine Strobl (SPD) having signed the final acceptance report in late 2013. © LiMux Project |

In 2002, when the first investigations into alternative solutions for Munich's IT departments started, this future success was not at all clear. In fact, when the Munich city council gave the green light on 28 May 2003 even independent analysts considered it a daring and risky strategy. The city had to overcome a lot of criticism over the years, as experts with all kinds of backgrounds – political, technical and administrative – raised their voices, doubting that LiMux could ever become successful and predicting that costs were bound to increase dramatically. Extensive discussion in the media even extended to reports in popular US newspapers such as USA Today, in June and July.

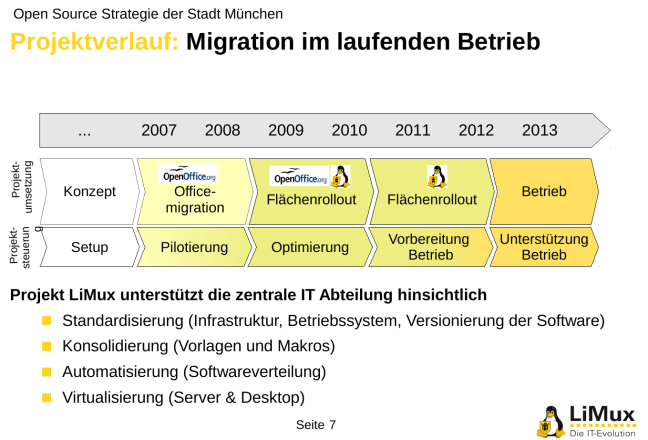

The basic LiMux timeline was:

- 2001–2003: first plans and discussions

- 2003: project started

- 2004: official order given

- 2005: the LiMux project started officially converting PCs

- 2008: the external consulting company could not meet the project's requirements and was replaced

- 2008: TüV Germany certified the LiMux desktop client as user-friendly and compliant with German usability standards

- 2008/2009: pilot phase, office migration

- July 2011: a party (the Bergfest) was held to mark the migration of half the total of machines planned

- Late 2012: initial goal of 12,000 Linux-based machines achieved

- October/November 2013: Final acceptance documents signed, regular operations mode started, 14,800 machines migrated to Ubuntu Linux and LibreOffice.

There were certainly no guarantees at the start. Back in 2002/3 only a few big administrations had dared to switch away from Microsoft infrastructures. But, as Munich employees continue to explain at conferences, it had already become predictable that in the years to come vendors such as Microsoft would increasingly strive to lock in their customers and squeeze revenues from them.

Infrastructure tools would become one of the weapons of choice: as Peter Hofmann often says, migrating from Windows NT to Active Directory or similar centralised software components would have brought ever-growing subjection to a single vendor whose only interest is – naturally – in making money. Exchange, SharePoint and public key servers would further tighten the straps with which the IT corporations strangled their customers.

No alternative?Surprisingly to many analysts, and often reported wrongly, money was never the main argument in persuading the politicians of Munich to agree to open source. On the contrary, when they were presented with the idea in 2003 the mayors and councillors were much more appreciative of the fact that the timing of any future upgrades would be under their control. For decades the politicians had been accustomed to agreeing to spend millions of Euros (or Deutschmarks) on some obscure new version of a Redmond product whenever their administrators told them that there was no alternative and that they needed to upgrade. The admins, of course, were simply passing on the same story from their Microsoft account managers. But with Linux, for the first time, the admins were able to let the politicians do what they love best: make decisions, feel important. And the Munich IT staff could offer a new strategy, something like: “If you choose this route now, in the future we will have true freedom of choice and you will be asked to make decisions more often.” From a non-technical point of view that translates to: “You will have more power to decide.” This shift of power did take some getting used to. Insiders report that council members' reactions ranged from distrust, through disbelief, to firm opposition. The latter was not really a surprise, given that Microsoft's German headquarters is located in the Munich suburb of Unterschleißheim. Rumour has it that Microsoft's plan to move its office to central Munich in 2015 is motivated by the loss of the municipality as a customer. |

Initial obstacles

There were also huge technical obstacles to address. In 2002 the open source community was very different from that of today. Though Android devices, Linux servers and embedded systems are now ubiquitous, comparable solutions could not be found on enterprise desktops in the early years of the millennium.

True, Linux had just celebrated its tenth birthday and IBM had embraced the world of free software with its first billion-dollar commitment. But the world of Linus Torvalds' operating system was still nerdy, programmed by geeks connected over the internet, and only later supported by companies with enterprise-level contracts.

Nevertheless, in 2002 the city of Munich began a year-long study phase that yielded a somewhat surprising result: purely in terms of quantifiable costs, the choice between a Microsoft-only and an open source solution would end up as a tie. At that point, strategic, political and ideological (“free instead of locked-in”) arguments became crucial to the decision. No matter that the city of Munich suspected that the free version would also be far cheaper than the proprietary system, money was never the main argument.

Infrastructure decisions

In January 2003 the city council accepted the plan to spend €30 million on moving its desktop PCs from Windows to Linux. At a time when a normal Linux migration was typically a move from Windows servers to Linux servers, keeping Windows machines as clients, this was a moderate sensation.

Because Microsoft would never offer a Linux version of its desktop software, the plan included migrating the city's office software (Microsoft Office) to a free solution (OpenOffice, and later LibreOffice). By moving away from the proprietary office product Munich would gain freedom of choice – which in this case led to the use of ODF, a free, XML-based office standard that is not subordinate to any vendor's decisions.

Thus the city council decided to aim for:

- a free and open source operating system, including office communication software based on open standards, for all desktop PCs in the municipality

- making, developing and/or procuring all administrative processes as platform-independent software

- creating a standardised IT platform, including consolidated applications and data store.

- Early in 2004 the migration itself started by introducing five goals for the IT administrators:

- migrating desktops from Windows to Linux in the form of the new LiMux desktop client

- migrating specialised administrative processes to free, web-based or native Linux solutions

- reducing complexity by consolidating the number of software products to the smallest possible amount

- transferring macros, templates and forms to the new solution

- Introducing system management software, deployment and a centralised sign-on mechanism.

These goals included setting up terminal services, web-based portals and a specialised Linux desktop operating system.

|

| One Linux migration project, 12 years of work: planning phase, concept phase and finally the migration. © LiMux Project |

Patent issues and the 2004 halt

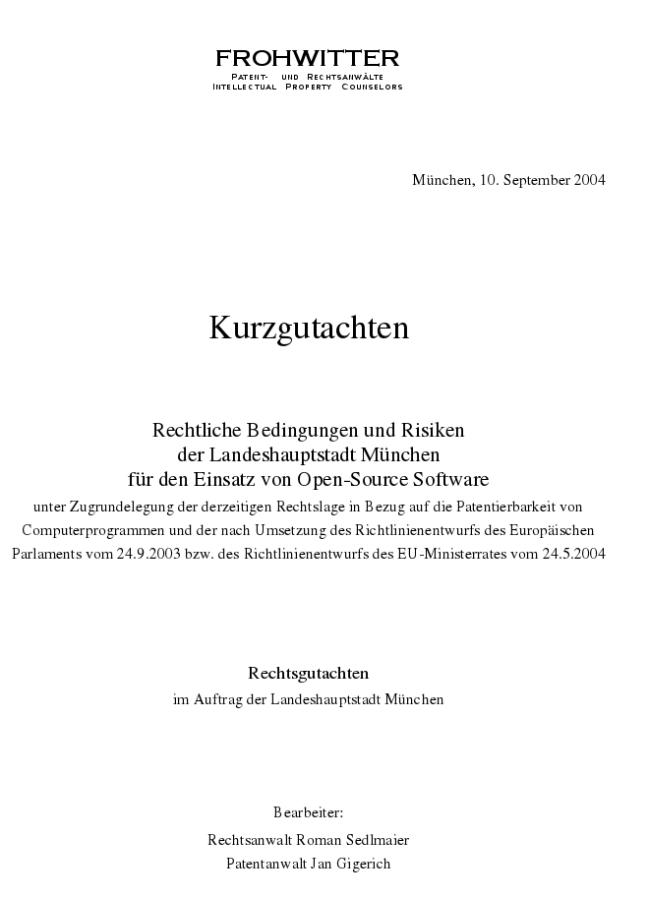

Technical questions and the problems of change management – both issues familiar to any other migration – were not the only difficulties Munich had to cope with. At various times legal and political matters also played an important role, sometimes to the point of endangering the whole project.

As early as summer 2004, an informal check of the patent situation had revealed that the Linux migration might be violating more than 50 European patents. These included Amazon's “one-click” patent and others covering JPEG, CIFS/SMB and XML, many of them held by Microsoft.

The Munich municipality stopped the migration project and consulted the city's patent lawyers, Frohwitter. By September 2004 the firm had produced a study concluding that software patents are likely to pose a low risk to free and open source software. Anyway, as Munich analyst Eitel Dignatz put it: “With its open source strategy Munich has a huge advantage: they can change. The room for manoeuvre is far bigger than with proprietary, vendor-locked products.”. Dignatz considered the whole discussion a piece of the silly season ("Sommertheater"), aiming at influencing the European Union's ongoing political discussion on software patents.

With that important point clear, the LiMux project could continue. To this day, many other municipalities are counting on the validity of Frohwitter's study.

Procurement, timing and project extension

This forced downtime was not the only delay to hit the project. Procurement, including the creation of procurement rules that had not previously existed, had taken more time than expected. In particular, the municipality's needs for support and maintenance of the new LiMux client were “difficult to describe”, said Manfred Lubig-Konzett, at that time deputy project leader.

“Munich was the first city ever to create a procurement system like that,” he continued. “We knew there were many eyes watching us, so we had to produce a comprehensible solution, perhaps more than others. And this suite had to fit from the start; we could not afford to present a bad solution. So in our plans quality took priority over time.”

The procurement took place in two steps. Autumn 2004 saw the launch of a bidding process in which 33 companies of all sizes took part. Some months later the city officials met representatives of six of these firms to start proceedings in more detail. Manfred Lubig-Konzett says: “Yes, you can have several rounds of negotiations. You don't need a functional specification document (Pflichtenheft) weighing seven pounds beforehand. And you don't have to choose the cheapest offer right away.”

|

| In 2004, Munich lawyers attested that free software was no more likely than proprietary software to be affected by European software patents. |

Gonicus and Softcon

Lubig-Konzett continued to explain that during negotiations all the participants were introduced to the various criteria and the weightings that the city addressed to these. Most important to LiMux were connectivity with the existing servers, office functionality, support and maintenance. It took two rounds of discussions before two middle-sized German companies, Softcon (Munich) and Gonicus (Dortmund), were accepted.

The city of Munich also started to recruit skilled Linux technicians. Just six out of 500 applicants were accepted, and together with employees from other departments they created the initial LiMux team of 11 open source specialists, supported by two consultants from Gonicus. In March 2005 they moved into a dedicated office and began work on the LiMux Basis Client, as the desktop operating system is known.

They made rapid progress, so that later that year deputy project leader Florian Schießl was able to show the first working version at the Systems industry fair in Munich. By 2006 the migration phase had begun. In the course of the migration many other companies, from the giant IBM down to several local Munich enterprises, helped with LiMux development, training, consulting and project management. Munich city politicians continue to stress that this proves their claim that the decision to use free software would strengthen local businesses.

Desktop Number OneBy 2003 it was clear to everybody involved that LiMux would require an enduring commitment from both IT specialists and politicians. General perception has it that few administrations think in decades, so public opinion was rather sceptical about the long-term chances for this new lighthouse project from the Linux community. Looking back, this is probably the part of the whole LiMux story in which fortune played the most important role. Unlike other (mostly German) open source projects, in Munich there had always been people in charge who agreed with their IT specialists that the open source path was best. Without a “Desktop Number One” making the first moves over and over again, setting a good example and showing his colleagues “It works!”, the LiMux project would probably not have been very successful. At this Desktop Number One sat Munich's Mayor Christian Ude, who used his political influence to promote the achievements and advantages of the open source decision despite all obstacles and attempts to persuade him otherwise. |

“Friendly” visits

In 2003, for instance, Microsoft CEO Steve Ballmer even broke off his skiing holiday to visit Munich and try to convince Ude that a Microsoft solution would be better. Though Ballmer offered to reduce licence prices – by 35 percent, from US$ 31.9 million to US$ 23.7 million, according to USA Today – he was obviously not convincing. By that time Microsoft had had to acknowledge the dangers of free software. A few months before, Ballmer had called Linux “a cancer that attaches itself in an intellectual property sense to everything it touches”; in the same year his sales representatives told their staff under no circumstances to lose against Linux.

But Ballmer wasn't the only one who tried to persuade Ude of a better solution. When the Munich mayor was at a conference in California, giving a speech about LiMux, Bill Gates was there as well. Ude, who is well-known as a humorist, loves to tell what happened next. Gates asked Ude if he would accept a lift to the airport in Gates's limousine. Wanting to save time, Ude agreed and off they went. Once in the car, however, the mayor discovered that the Microsoft CEO wanted to use the 20-minute ride to talk him out of LiMux. Gates asked: “Mr. Ude, why are you doing this?”. Ude replied: “To gain freedom.” Gates: “Freedom from what?” Ude: “Freedom from you, Mr. Gates.” According to Ude the rest of the ride passed in silence.

|

| Christian Ude Munich's mayor (“Oberbürgermeister”, SPD) accompanied and supported the LiMux project for more than a decade. © City of Munich, Christian Ude |

The old IT

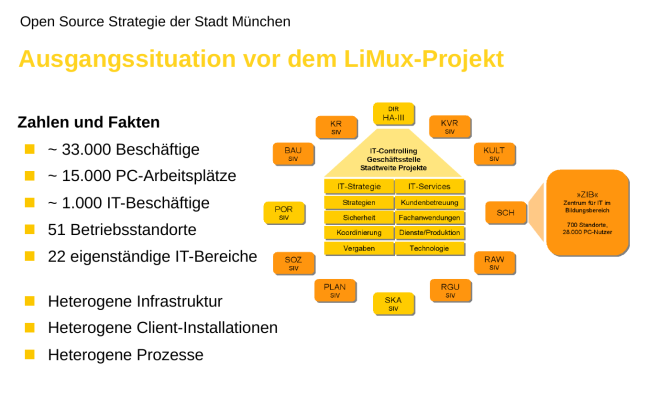

Back in 2002 the city of Munich's IT systems presented a very heterogeneous landscape. More than 16,000 users worked with Microsoft NT and various versions of Microsoft Office. There were 340 specialised administrative processes, half of them mainframe-based. On top of that, administrators found more than 300 other software products on the city's desktops. File services came in two separate flavours: one Netware-based, the other specific to the Windows NT domain.

Munich, the third-largest city in Germany as measured by its population of 1.4 million, has a rather complex IT organisation. 22 separate migration units plan and operate their own infrastructures, with central coordination for IT strategy and procurement. As in other complex environments that have grown up over time, there were many different structures for user management, support and almost every other aspect of IT.

These differences later led to the creation of a project known as MIT-Konkret to provide a new strategic focus for the Munich IT departments. MIT-Konkret had three goals:

- keeping the decentralised organisation as close to its customers (citizens and employees) as possible

- centralising all technical and planning decisions in a newly formed department known as IT@M

- bundling the overall strategy within STRAC (“IT-Strategie, IT-Steuerung & IT-Controlling”), a unit combining IT strategy, technical direction and financial oversight.

All of the above is part of the concept of “Kernkompetenzfokussierung” (KKF). This means focusing on the central components of each department's competences, using the same processes across the various Referates to deliver high-quality IT services to both employees and the citizens of Munich. “Munich city IT supports the business processes of all its departments with professional IT services” is the credo of the city's administration.

LiMux: From Debian to Ubuntu

A newly developed, specially adapted open source operating system was required as the central component of the new Linux-based desktop. In the beginning, following recommendations from people including former project leader Florian Schießl, Debian Linux was the first choice for that operating system.

Within months of the city's decision to adopt open source, the KDE project – a window manager plus lots of applications delivering an easy-to-use desktop experience to new users – had released its third edition (April 2003). Many analysts believed that this was the first version suitable for enterprise use. LiMux went for KDE on Debian because this distribution was one of the few not connected with companies like Suse or Red Hat. The Debian project is controlled entirely from within, free from any marketing decisions and driven completely by volunteers connected over the web.

But the choice of Debian sparked a controversy within LiMux and among its supporters. Both Suse and IBM had been helping the city of Munich to define its strategy, yet in the beginning neither company could take part in the project.

Another issue was that Debian could not promise regular updates. The Debian project follows the open source dogma: “It's done when it's done”. Each new version of Debian appears when all the developers are happy with its quality, not necessarily in compliance with a deadline.

Many years later, the city decided to switch to Ubuntu Linux, a Debian derivative with scheduled, plannable updates. Canonical, the company behind Ubuntu, promises to deliver a new version twice a year (April and October), and offers long-term support for special versions. Canonical promised five years of support for Ubuntu Linux 10.04, the version chosen by LiMux.

Furthermore, Ubuntu comes with a more up-to-date software selection than the rather conservative Debian distribution. Arguments like that made the LiMux project switch horses in 2011, starting with Ubuntu 10.04 and KDE 3.5 for its LiMux Client Version 4. In August of that year release manager Robert Jähne announced the new version, which had been created within a year with extensive help from IBM's project management team. In contrast to the Debian solution used until then, the new version could support up-to-date hardware easily and brought many new software packages to the desktop in one go, according to Jähne. The switch to Ubuntu thus enabled support, regular updates, and the ability to add newer hardware drivers – an important point for the procurement of new hardware.

|

| KDE 3.5 on Debian Linux, later Ubuntu: an early LiMux desktop at work. © City of Munich |

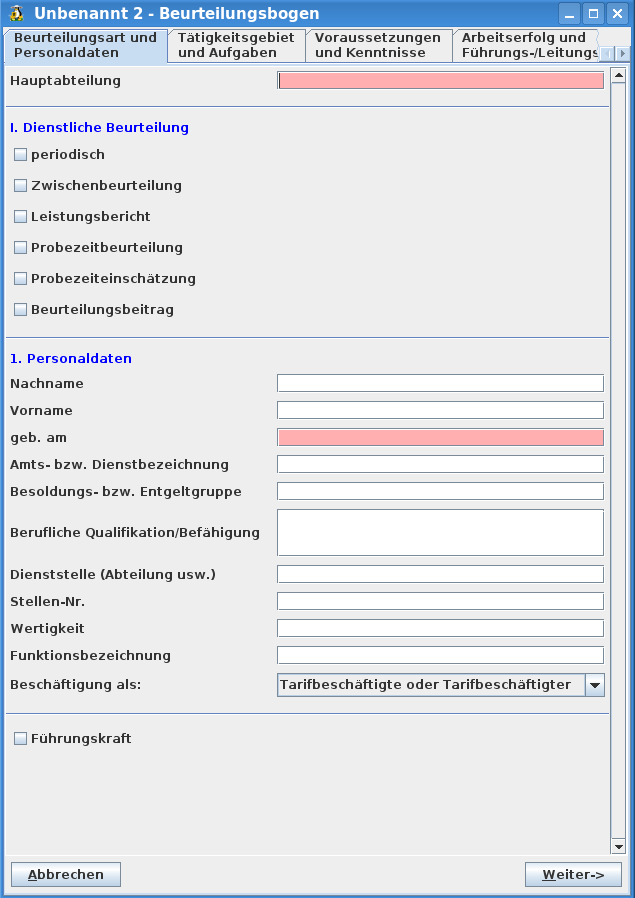

KDE as desktop of choiceThe LiMux desktop client provides a graphical user interface with a classic start menu. Here users find the software tools that in recent years have become standard on operating systems from Windows to Mac OS X and Linux: the Firefox web browser, the Thunderbird mail client, GIMP for image processing, Acrobat/Adobe Reader for PDF presentation, and of course OpenOffice, later LibreOffice. The last of these are free office suites providing workable yet standards-compliant alternatives to Microsoft Word (Writer), Powerpoint (Impress) and Excel (Calc), plus tools for painting and drawing (Draw) and other functions. To manage macros, templates, forms and documents the city had to develop its own centralised software, known as WollMux. |

Office migration: a big challenge

When the LiMux project started, most of the people responsible thought that migrating the operating system itself would be the biggest obstacle. However, there were other hurdles to jump.

One of these, and perhaps the toughest job of all, turned out to be the switch from Microsoft Office to OpenOffice/LibreOffice. At some point during the planning phase the administrators had to acknowledge that they had never previously had a clue how many individual macros, templates and forms were crucial to the daily work of the city's departments. When the migration team started to make lists, more and more of these Microsoft-specific add-ons popped up, with nobody remembering who had programmed them and no information about how they worked. Project representatives started to call them U-Boote (submarines), since they seemed to appear from nowhere. A typical problem started with an employee saying: “I don't know, all I am doing is hitting STRG+SHIFT+F4 all day.”

|

| 33.000 employees, 15.000 seats, 1000 working as IT staff, 51 branches, 22 migration units: LiMux is big. © Limux |

In the end the team identified 21,000 templates and 900 macros across the 22 departments. They had been developed over many years in different programming languages and by different people with different skill levels. Very often the original developers were no longer at work or could not be identified. This meant that an automated solution, as some companies were offering, was not feasible. The city was forced to choose a different path that in the end consolidated the mess into 12,000 templates, 38 new web-based processes and 100 macros – all now quality-managed, tested and documented.

Kirsten Böge, Communications Manager for the LiMux project, outlined the new approach in a conference speech in 2012. To cope with the uncontrolled numbers of macros and templates from 2003, she said, the organisation had set up a centrally managed process with five main achievements:

- All macros were now organised in a central repository with quality management and documentation

- ODF was chosen as the standard format for office documents and templates

- Overall the number of macros, templates and forms had been cut to 40 percent of the original figure

- The heads of IT departments and the municipality now had full control over macros, templates and forms

- Munich was now supporting other communities and municipalities with office elements created for their daily use.

All of this was possible because the representatives chose a six-step path that can be seen as a blueprint for the whole LiMux migration project.

The first step was to identify and count the macros, templates and forms (“office objects”) to be migrated. Second was to eliminate duplicates. The third step was to migrate the remaining objects to the new office software. It was considered crucial to the success of the migration to get direct feedback and quality control from the people who would have to use the new workflows, and also to set up an independent quality assurance process.

At this point it became clear that the migration of the office software and that of the operating system should be handled independently. The fourth step was therefore to choose a soft migration strategy. Since a direct connection to individual employees working with the new desktops had been identified as crucial to success, from both a technological and a social, motivational point of view, a “germ cell” strategy was set up (the fifth step) and the migration was started in separate blocks (sixth step).

Germ cells

Classic approaches to IT migration try to minimise expenses by calculating training costs with regard to the skill level of the users: less-skilled people need more training. The LiMux project experienced different problems. Especially when discussing emotional topics like “the best desktop operating system” or “the best approach in IT”, it proved difficult to convince sceptical staff members of the benefits of the new solution. Training the sceptical and less-skilled staff would not help here, so the project leaders chose a “snowball” or “germ cell” strategy instead.

Böge explains how the LiMux team identified one small office with a clear, one-dimensional workflow and few administrative processes. They introduced the new desktops here first and then identified Migrationsbereiche (realms of migration) in the form of other departments with similar workflows. The first workers to adopt the new systems (both office and Linux) in these other departments then acted as “germ cells”, collecting experience and acting as (hopefully good) examples to their fellow workers. The aim was for the migration to grow like a snowball in front of the eyes of the sceptical or unmotivated users.

In the end it worked out, says Böge: they finished on time and 20 percent below budget. Other gains are difficult to count in monetary terms: the city now has guidelines for office objects, clearly defined migration processes for old objects, a documentation model and a standardised repository. All that adds up to “highly improved maintainability of all of our office objects”, Böge says.

WollMuxApart from the social and organisational aspects, the office migration also gave rise to WollMux, a template and form manager developed by the city of Munich and since given back to the upstream community. The name is a Bavarian idiom that needs a little explanation. Its long form is “Eierlegende WollMux”, an allusion to a fantasy domestic animal that gives meat, wool, eggs and milk. By analogy, WollMux is supposed to do everything the city of Munich needs in the vast field of office document automation. WollMux allows employees to choose templates for their work with customers, filling them automatically with centrally stored data and thereby providing completely accurate documents and printouts within minutes. As WollMux has been published as open source, any other community or organisation can download, use and modify it.

|

Project management

As a side effect of the migration project the city of Munich was able to install a completely new governance model for IT. Role-based, distributed and extended step-by-step to its current state, the new model is based around several working groups at different levels: Lenkungskreise, Projektgruppen and Beiräte. The Lenkungskreis (LKr) is the supreme decision-making organ. It is backed up by a so-called “3+1+2 Beirat” composed of people from the various migration groups (Migrationsbereiche).

For technical matters a central LiMux project group is supported by specialist working groups (Projektgruppen) representing the Linux client, office software, test management etc. A change advisory board keeps track of all changes deployed to the departments, though this is scheduled to be replaced by a more systematic method of managing changes, requirements and releases, including a quality assurance plan.

The city of Munich has developed clear processes to manage communication within the new governance model. Every two months the LKr meets to discuss the project's progress. The members agree on intermediate and annual goals, and look for solutions to any serious problems that may have arisen.

Whereas the LKr meetings represent the operational view, the lower-level groups focus on information exchange and specific solutions. That way even basic decisions like whether a “big bang” or a “soft migration” is better for a particular department are delegated to the department itself. For instance, one Referat might start by installing Firefox, Thunderbird and OpenOffice on Windows machines (soft migration). Another could introduce the Linux client and all of its desktop tools at the same time (big bang). The only common procedure was the introduction of germ cells, as discussed above, across all departments. By migrating these small, simple and clearly structured workplaces to the new products, the department's admins and staff could collect experience and spot problems later on.

All of the above took place in parallel. By 2009 all personal computers had been equipped with OpenOffice. Starting with the client versions 2.3 and 2.4, more and more machines were migrated to Linux. Version 4.0 (2011) brought updated versions of Thunderbird, Firefox and OpenOffice 3.2.1 to more than 8,000 seats. In October 2012 Kirsten Böge announced the move towards LibreOffice at the LibreOffice Hackfest that took place in Munich.

As of late 2013 the LiMux core team consists of about 25 people working exclusively on the Linux client, office migration and WollMux. An “extended project team” involves “many colleagues from all departments and migration tasks who are supporting users every day”, explains Munich's IT architect for the Linux desktop, Jutta Kreyss. This approach has proven to ensure direct feedback and to give the staff the best possible feeling that the IT departments are treating their problems seriously. Most important of all the social factors, it emphasises the central role of users and confirms that “we are doing what we are doing only to make the employees work easier and better, every day”, Kreyss says.

E-learning and training

Recognising the importance of soft or human factors within the migration is one of the most crucial insights of the LiMux project. That insight has affected many procedures over the past ten years. Training, deployment and support were all adapted (sometimes admittedly in a rather symbolic style) to emphasise that “we are doing all this to make your work easier!”.

Training, formerly run as classic 4-5 day all-in-one classes for everybody, has been recast in the form of shorter sessions tailored to the daily work needs of employees and their departments. Examples range from basic office topics to intermediate and advanced training in form letters.

Once the administrators and technical staff had received their training, ordinary users were able to take advantage of a completely new e-learning environment, the “LiMux Learning World”. Here users can choose the software products they want to learn about and control the pace of the training. In 2007 the LiMux Learning World received the eureleA European e-learning award.

Cost

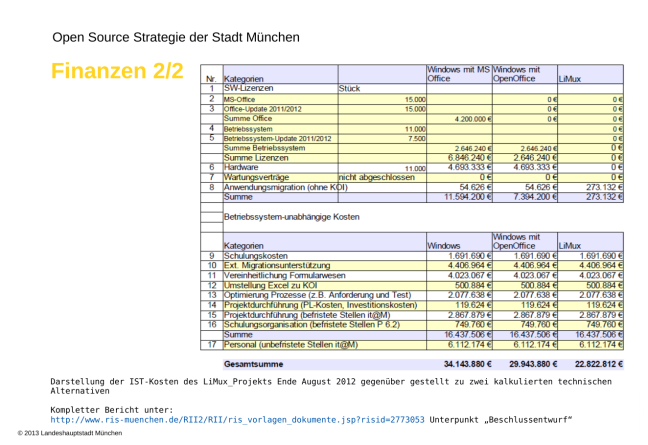

|

| Detailed figures of the LiMux project reveal differences from the original plan. Despite the economic success of LiMux, money has never been the driving factor. © Limux |

When the LiMux project officially started in 2005 it was scheduled to take four years and to cost €12 million. It was planned as a city-wide project, run by the departments and not by the central IT administration services.

In 2007 the project had to be extended. While the budget remained the same, the target completion date was now 2011. Its structure also changed: while the departments would still do the work, LiMux would henceforth be coordinated centrally.

The extension in 2007 took into account the need to consolidate the project's infrastructure. By 2009, however, it had become clear that it was not possible to adapt the new clients to the existing, old and heterogeneous servers.

Even more importantly, the chosen contractors could not provide the required solutions, at least not at the quality level necessary. After several interventions the city of Munich cancelled the contract, and in 2010 the LiMux project had to be extended once more. It had become clear that LiMux would not finish before 2013, at an estimated total cost of €18 million.

The increased budget now included external costs for consulting, and several new extensions to the original project. From 2010 on, for instance, LiMux included a new project management structure (the 3+1+2 group etc.) and architecture, testing, requirement and release management. All of these were completed by the end of 2013.

In his final report, project leader Hofmann explains: “Even though the project timescale was extended by 80 percent from five to nine years, the cost only rose by 44 percent (from €12 million to € 18.7 million).” The distribution of costs reveals some interesting aspects:

- costs for applications were far lower than expected, because much more could be done with free software or local solutions (like local virtualisation) than initially predicted

- expenses for internal staff were lower than expected, in part because there were not enough applicants for all of the jobs

- external consulting costs were much higher than expected, because of both the lack of internal staff and missing technical knowledge within the municipality's administration.

With all this in mind, the municipality has achieved:

- An extraordinarily high level of independence from vendors

- Independence in its operating system

- The overall use of open standards as normal practice

- A very high level of IT security

- No shutdowns of any services or processes over a migration period of several years

- OpenOffice or LibreOffice installed on more than 15,000 desktops, including Windows machines

- Office objects have been reduced by 40 %, of which macros could be reduced to 20 % of the original amount, all consolidated into Web- and Wollmux solutions

- Organisation, project management, testing, release and configuration management, deployment, rollout and centralised services successfully introduced.

Important lessons

In their final report the LiMux project officials set out eight points that are crucial to a migration as large and unprecedented as the Munich case:

- Political support is crucial. Without a person like Mayor Ude, and similar supporters at all levels of the administration, the whole process would have failed. The ability to stand up to lobbyists and handle conflicts without cancelling the project is vital. An interview showing Christian Ude's commitment can be found here.

- Migrating PCs and networks is an ongoing project, not a single step. Acknowledging that migration is a long process, not a “big bang”, has been another important lesson.

- Staff are important. A migration project starts with the IT staff. Motivation is absolutely crucial for both IT staff and users, and needs care and organisation. People have to feel that the project is meant to improve and ease their daily work.

- Respect all levels of organization. The LiMux project had recognized that leaders on all levels of organization were important for the whole project, because their positive role model would have a very strong impact on the motivation of the IT users before and during the migration.

- In most cases, projects like these cannot be planned in advance. The first steps have to be to count, identify and structure the existing IT landscapes. One of the most important benefits for the city of Munich was the reorganisation of the IT structure. For the first time, the admins would know exactly by whom, where, when and why a programme was running – not as a matter of control, but for organisational and quality assurance purposes.

- Beware of heterogeneous IT landscapes. They are far more complex in terms of both administration and migration.

- Professional management of requirements, testing, releases and patches is fundamental.

- Again: Only motivated staff can do this. Keeping staff motivated is a very important factor.

Community

But LiMux is no longer alone. Both the Linux desktop client, with all of its automated deployment and configuration management tools, and the office solution with WollMux are published under open source licenses which allow other entities to use and adapt them. And if other municipalities want to do so, they can have support from the city of Munich. In terms of office migration Kirsten Böge sets out three goals for the near future:

- extend and promote the use of ODF (the standards-compliant and open document format used by OpenOffice/LibreOffice) to other cities

- integrate with other municipalities towards open macro/template/office standards

- present the success of LiMux and WollMux through congresses, events, tutorials and training.

In the end, hopes Böge, many municipalities might join Munich to develop open source software that is perfectly adapted to the public sector. Although with the completion of the LiMux project ressources for these tasks have been reduced, the community work is still an important aspect of the Munich IT staff - knowing that their success is partly a product of the open source community. The LiMux team still joins events, trade fairs and holds lectures about the project and sparks crowd-sourced office feature development, but not as actively as they had been during the migration.

The future

LiMux is finished, but the work continues. There are still some technical details to see to: migrating many machines from OpenOffice to LibreOffice, creating new and improved test procedures in software development, and migrating a few machines that up to now had been excluded for technical reasons. But even that is not the end of the story, says Peter Hofmann. All of the migrated machines and the new software systems need to be checked and steadily improved, new software needs integration, new requirements have to be met.

In the years to come the Munich IT departments will focus on projects like MigMak (establishing a free and open source groupware solution), integrating mobile devices and tablets, providing more and more free WiFi access for the citizens of Munich and distributing Linux to them.

Starting in September 2013, the LiMux project has provided its citizens with free Ubuntu Linux DVDs as a signpost, regarding Microsoft's announcement to stop support for Windows XP in April 2014: “There are alternatives, and they work!”