This chapter aims to help those that are responsible for interoperability assessments within their public organisations to decide whether they are legally obliged to carry out an interoperability assessment.

It specifically unpacks the IEA concepts that trigger the obligation to conduct the interoperability assessment. Building on an in-depth explanation of these key concepts, a decision tree summarises the steps to take to understand whether an interoperability assessment is required. The concepts are further illustrated with a number of examples in the form of cases where one may or may not be obliged to undertake an assessment.

2.1 The main concepts in the context of interoperability assessments

Interoperability assessments aim at a well-managed change process in which impacts on cross-border interoperability are identified as proactively as possible. Article 2 of the IEA defines the main concepts:

The concept of ‘binding requirements’ is defined in Article 2(15) IEA as:

- an obligation, prohibition, condition, criterion or limit;

- of a legal, organisational, semantic or technical nature;

- which is set by a Union entity or a public sector body;

- concerning one or more trans-European digital public services; and

- which has an effect on cross-border interoperability.

What the IEA says

Recital 18 IEA further specifies what a binding requirement is and how it can be set: Binding requirements can be set within ‘a law, regulation, administrative provision, contract, call for tender, or another official document. Binding requirements affect how trans-European digital public services and the network and information systems used for their provision are designed, procured, developed, and implemented, thereby influencing the inbound or outbound data flows of these services. Tasks such as evolutive maintenance not introducing substantive change, security and technical updates, or simple procurement of standard ICT equipment do usually not affect the cross-border interoperability of trans-European digital public services and do therefore not result in a mandatory interoperability assessment within the meaning of this Regulation’ (Recitals 10, 15-17 and 21-22 IEA are also relevant)

When assessing if a requirement is ‘binding’ according to the IEA, one essential factor is whether the requirement has consequences for other organisations taking part in the provision of the public service (i.e., an effect on cross-border interoperability). For instance, a technical requirement that becomes mandatory only for the deciding party but still limits the choices left to others can be considered a binding requirement.

Binding requirements will usually arise from legislation. A binding requirement in a law could, for example, concern:

- the collection, processing, generation, exchange or sharing of data between Union entities or public sector bodies (e.g. a regulation on public registries);

- the automation or digitalisation of public services or their underlying processes (e.g. the use of AI in a public service or providing a driving licence in a digital format (as data) instead of a physical card);

- the use of new or existing network and information systems (e.g. the use of the ‘once-only’ technical system - See Article 14 of the Single Digital Gateway Regulation).

For example, EU legislation that obliges Member States to coordinate the execution of different national government tasks will often require to develop – or modify significantly – as well as integrate information systems or other digital solutions such as APIs (Application Programming Interfaces are software intermediaries that allow two applications to communicate, i.e., enable data transmission) in order to support the new requirements. EU legislation that contains binding requirements includes, e.g., the Single Digital Gateway Regulation (requirement for additional layer to be added on the top of national infrastructure), the eIDAS Regulation (requirement to adjust national services) and Schengen legislation (requirement to fully harmonise systems).

Spending on significant development of information systems often requires a mandate through a budget allocation. Moreover, new data flows between authorities will often require a legal basis for the exchange of data. It will therefore generally make sense to pay careful attention to any requirements that are part of a decision by a legislator. It is nevertheless important to keep in mind that public sector bodies or Union entities may in some cases decide to establish binding requirements outside legislation (e.g. requirements in procurement procedures, large scale pilots or in bilateral agreements between two or more Member States).It is also possible that, after the binding requirements from the initial legislation have been assessed, additional requirements may be set (e.g. specifying the digital public service delivery). Such decisions might limit the choices left to others and would therefore need an interoperability assessment as well.

Generally, no assessment will be needed for instances that concern tasks such as evolutive maintenance that do not introduce substantive change, security or technical updates, or the simple procurement of standard information and communication technologies (ICT) equipment (Recital 18 IEA).

Going beyond the binding nature, a ‘binding requirement’ in the meaning of the IEA would also need to be set by a Union entity or a public sector body, concern one or more trans-European digital public services and have an effect on cross-border interoperability. These concepts are explained further below.

The binding requirement(s) assessed need to be set by a public sector body or a Union entity. Article 2(6) of the IEA defines a ‘public sector body’ in the same way a public sector body is defined by Article 2(1) of the Open Data Directive, namely:

- State, regional or local authorities;

- bodies governed by public law (see the definition in Article 2(2) of the Open Data Directive); or

- associations formed by one or more such authorities or one or more such bodies governed by public law.

This definition is used not only in the context of the Open Data Directive but also for the eIDAS Regulation. Consequently, a public organisation that falls within the scope of those legislative acts also falls within the definition of a public sector body according to the IEA.

Article 2(5) of the IEA defines ‘Union entities’ as ‘the Union institutions, bodies, offices and agencies set up by, or on the basis of, the Treaty on the European Union, the Treaty on the functioning of the European Union or the Treaty establishing the European Atomic Energy Community’.

Services are to be considered trans-European digital public services when they fulfil the cumulative requirements set out in Article 2(2) of the IEA. In other words, the services are:

'Digital services provided by Union entities or public sector bodies to one another or to natural or legal persons in the Union, and requiring interaction across Member State borders, among Union entities or between Union entities and public sector bodies, by means of their network and information systems.’ - Article 2(2) IEA

Only binding requirements concerning such trans-European digital public services have to undergo an interoperability assessment. This means the requirement should affect how the trans-European digital public services or their networks and information systems are designed, procured, developed, implemented and delivered, thereby influencing the inbound or outbound data flows of those services. In other words, the requirement should affect the data involved, considering from whom it goes to whom and by which digital solution. Incoming data flows can be composed of:

- the data needed to deliver the digital public service,

- from whom it is received,

- and the digital channel by which it is received

Outbound dataflows can be composed of:

- the data delivered by the digital public service

- to whom it is delivered,

- and the digital channel by which it is provided

What is a digital public service?

In order to further understand the concept of trans-European digital public service, it is important to understand the underlying concepts on which it builds. The IEA applies only to digital public services but does not define which services are to be considered public services. Article 1(3) specifies that ‘This Regulation applies without prejudice to the competence of Member States to define what constitutes public services or to their ability to establish procedural rules for or to provide, manage or implement those services.’ This means that not all public services will be the same across all Member States.

However, there are some shared characteristics: digital public services within the meaning of the IEA are only services provided either by Union entities or by public sector bodies of Member States. For instance, private companies may manage a carpark on a public ground and a parking app supporting such a service. The mere fact that the physical space is owned by a public sector body and that these private companies rent it from this public sector body does not automatically mean that the digital parking applications are digital public services provided by a public sector body. In other cases, private sector bodies may perform an auxiliary role which does not impact the public nature of a service (for example, a public service may use cloud services provided by private sector bodies, but the public sector body or Union entity retains overall responsibility for providing the service).

Trans-European digital public services are limited to services that are provided either to another public sector body or Union entity, or to a natural or legal person in the EU. This means that requirements that concern services that are available only for internal use within a public sector body or a Union entity do not fall within the definition (e.g. booking a table in an open office space) and nor do services that only involve interaction with a country or citizens and businesses outside the EU.

What makes a digital public service trans-European?

If the concerned service or services meets the requirements for being a digital public service, it is then possible to assess whether it also constitutes a trans-European digital public service. This involves meeting two conditions: (i) the service must involve interaction across Member State borders, among Union entities or between Union entities and public sector bodies, i.e., across their jurisdictions and (ii) it must do so by means of their network and information systems.

Examples of interaction across Member State borders could be interactions needed for the mutual recognition of academic diplomas or professional qualifications; exchanges of vehicle data for road safety; access to social security and health data; and exchange of information related to taxation, customs and in general all those services that implement the ‘once-only’ principle.

Interaction among Union entities could, for example, include interaction between a Commission service and an agency to manage a project or a funding programme or the interaction between the co-legislators.

Interaction between Member State public sector bodies and Union entities could, for example, happen in the context of single window systems, public procurement above the threshold or different reporting mechanisms. Interactions that happen through systems that are provided by Union entities but support interaction across Member States borders would fall into both categories (e.g. interaction through the ‘once-only’ technical system).

The service must also require interaction between the network or information systems of two or more public sector bodies or Union entities. If the provision of a digital public service does not require interaction with networks or information systems of other public sector bodies or Union entities, then the service is not to be considered a trans-European digital public service. This is the case, for example, when evidence is exchanged by normal post.

The binding requirements in terms of scope will need to have an effect on cross-border interoperability as defined in Article 2(1) IEA. The question of how it has such an effect will be part of the assessment itself, but the question of its potential effect is part of the pre-assessment. If the requirements to be assessed concern trans-European digital public services (and, with this, interaction between public sector bodies in different Member States and Union entities), they will normally also affect cross-border interoperability, because they will determine the way in which the public sector bodies and Union entities interact with each other.

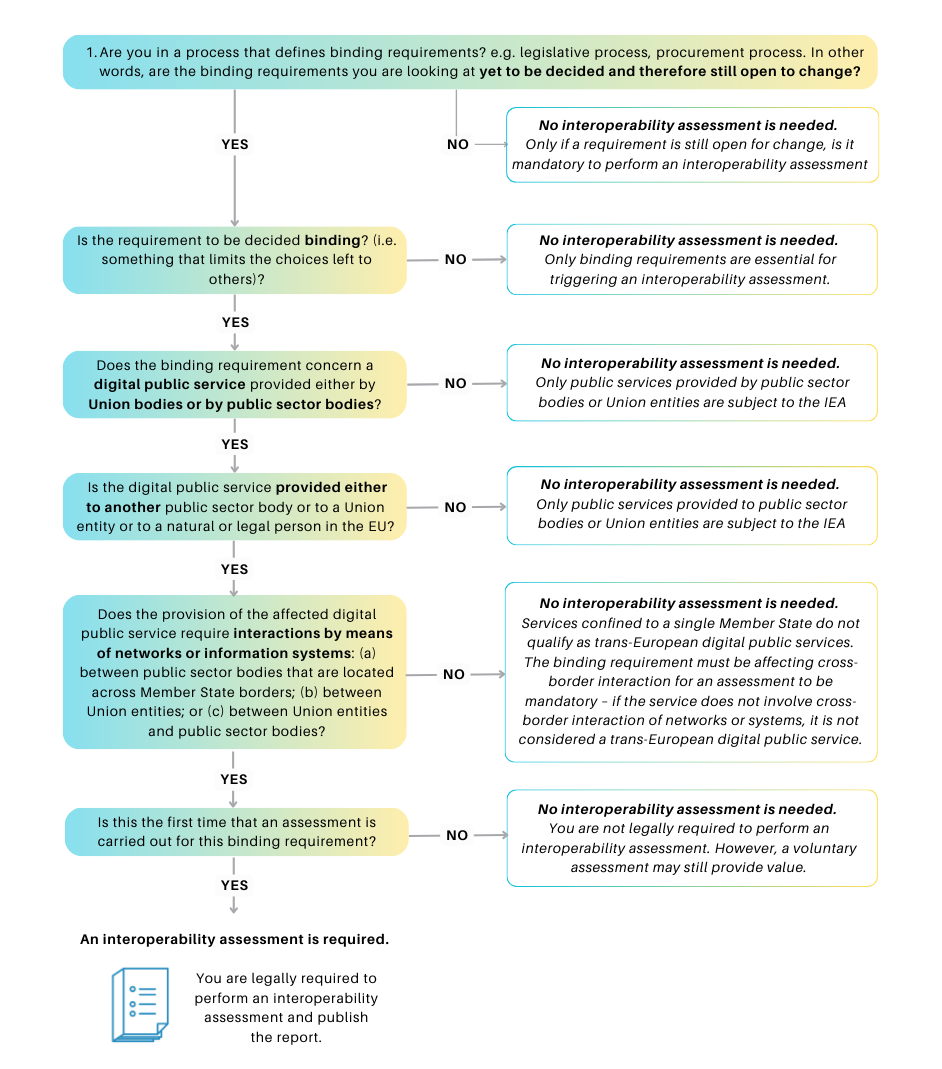

2.2 Decision Tree

The decision trees (interactive and static) below can be used as a basis for assessing whether an interoperability assessment is needed. If the authority arrives at ‘Yes’ in the decision tree, an interoperability assessment is mandatory. If it does not, an interoperability assessment is not mandatory but may still provide value (see Chapter 1).

Dynamic decision tree

Answer "Yes" or "No" to the following questions, and the form will automatically indicate you whether the assessment is or not mandatory:

Static decision tree

Irrespective of the result of the decision tree, it is important to consider the following three points:

No need to repeat

Only the public organisation that is planning a decision on a requirement is obliged to carry out the assessment. This is true for requirements at any stage of the life-cycle of a digital public service and might mean different entities, depending on whether the requirements are introduced in a legal proposal or specified later on (by setting new ones) during implementation or management of the service. If a file is under shared responsibility, the entities must agree on the roles and collaborate (see also Chapter 5). The obligation does not concern any public organisation that is simply implementing a requirement and is bound by the decision of another public organisation (see also Questions 1 and 2 in the decision tree). If a decision is taken jointly (e.g. in the context of a cross-border project), the assessment can also be performed jointly.

The rule that there is no need to repeat assessments is further clarified by the exemption in Article 3 IEA: there is no need to repeat the mandatory interoperability assessment for a previously assessed binding requirement. However, while there is no need to repeat assessments, different versions can certainly be related.

Related assessments

Specifically, assessments can build on each other when one public organisation (e.g. a Union entity) sets high-level binding requirements that are then further defined by the implementing entities. This could, for example, happen during the transposition of an EU directive into national legislation or when a previously assessed binding requirement adopted in a legal text is further refined in a public procurement procedure for its implementation. If this is done by deciding on new binding requirements, barriers to cross-border interoperability can also be introduced at this later stage, so the newly added requirements will need to be assessed. However, these assessments can reference previous assessments and build on their findings.

Following the same rule, no assessment at the implementation stage is needed when a binding requirement is to be implemented by solutions provided by Union entities. Here, it is assumed that all solutions provided by Union entities are interoperable by default as they are provided for a wide variety of contexts across the EU. In this case too, however, an interoperability assessment may be carried out voluntarily in order to verify that all the potential cross-border interoperability issues are addressed by these solutions in the specific context.

No retroactive assessments

The legal obligation to perform interoperability assessments enters into force on 12 January 2025. Many binding requirements affecting the cross-border interoperability of trans-European digital public services may already have been decided upon but not yet transposed or implemented. A retroactive assessment is not mandatory but is highly recommended for cases with high stakes, because it can help the transposition or implementation, as explained above.

2.3 Examples

Below are some examples of cases when assessments are/ are not mandatory:

A big city in a Member State needs to further develop its technical system to support extended requirements for data exchange with other Member States’ authorities that result from a new EU regulation.

However, the responsible directorate-general in the Commission has carried out a detailed interoperability assessment in connection with the submission of the proposal and this describes the expected consequences for the Member States. There is no need to carry out a new interoperability assessment if the intended change stems directly from the need to comply with the new regulation. In other words, a new assessment is not mandatory in this case because the city is not taking the decision but merely implementing a decision on binding requirements (see Question 1 (Q1) in Decision tree).

However, a new assessment would be mandatory if the city were to decide to implement additional requirements that do not stem from an obligation under the new regulation but would be set in the same context (data exchange across borders) or likely to affect it (change in data format or ownership).

A government agency in a Member State needs to have its reporting solution further developed in order to support new binding requirements that result from a recently adopted regulation. The regulation obliges actors that are active on the domestic market for product X to regularly submit digital reports on the sales of their product.

No assessment is required because the agency is not taking the decision but just implementing a decision on binding requirements (see Q1).

The situation would be different, however, if the regulation merely set a high-level requirement and the agency were planning to decide on further new binding requirements for implementation that have not yet been assessed. For example, the agency might have to decide on requirements regulating the sharing of the digital reporting of the sales and would then need to assess the effect of such a requirement on cross-border data-sharing.

The agency could still conclude that it is not obliged to carry out an interoperability assessment. The new requirement does not concern a digital public service (specifically not the interaction of such a service with others) but merely changes the threshold for the number of companies to be reported on (Q3). In this case, a voluntary assessment may nevertheless bring value.

A government agency in a Member State is about to put out to tender a framework contract for the maintenance and further development of its information systems. The agency is deciding on a binding requirement and not just implementing a decision (Q1).

Binding requirements may include a call for tender. However, the tendering of a framework contract for the operation, maintenance and further development of professional systems will not in itself contain binding requirements for digital public services, but rather ‘evolutive maintenance’ (Q2). There is therefore no need for an interoperability assessment.

An assessment will usually be needed if a specific system development is requested within the framework of the contract (e.g. a new national or organisation-specific requirement is introduced to support new legislation – this could have consequences for the cross-border interoperability of trans-European digital public services, perhaps because it changes (aspects of) the business logic of a system).

A municipality in the border region of a Member State is considering acquiring a digital self-service solution to enable payment for parking in the municipality’s designated areas. In connection with the procurement decision, the municipality will set new binding requirements for an information system to provide this service.

However, the requirements do not affect cross-border interoperability (Q3), because the solution is intended to request payment from the party, who wants to pay the fee for parking directly. No data exchange between authorities in Member States or with EU institutions is necessary in the transaction.

Therefore, because the delivery of the service does not necessitate the interaction of network or information services across borders, the municipality is not obliged to carry out an interoperability assessment before procuring the proposed solution.

A directorate-general of the Commission has drafted a legislative act to further regulate the agricultural sector by introducing new delimitations and data types for CO2 emission reporting. Several Member States already introduced national solutions for reporting two years ago. If adopted, the legislative act would require those Member States to further develop their existing legal frameworks and information systems so that they can support the new delimitations and data types described in the legislative act.

The directorate-general will have to carry out an interoperability assessment for the proposal because it is still open for discussion (Q1) and concerns a trans-European digital public service (Q2 and Q3) (i.e. it concerns data flows between public organisations). This interoperability assessment would then need to consider the existing solutions and how they can be (re)used and thereby avoid duplication of efforts and resources.

Apart from these concrete examples, the following instances are also good indicators for when an assessment is likely to be valuable, if not mandatory:

- setting new tasks for authorities

- changes in disclosure of information

- changes in rights to obtain information

- new way to provide the public service